Five Years Post-Rehab, $uicideboy$ Are ‘Grateful to be Alive’ — And Maybe Even Happy

Back in 2015, Scott Arceneaux Jr. was a common presence at New Orleans post offices. Online, Arceneaux was better known as “Scrim” — one-half of the emo-rap duo $uicideboy$, which was quickly becoming one of the hottest and most controversial new acts on SoundCloud, with songs about drugs, death and their own misery. But at the post office, he was just Scott, that nice, tattoo-covered guy licking envelopes from opening to closing.

Despite the many successes — and even more face tattoos — he’s accrued since those post office days, Scrim still clearly carries that same humble, hardworking mentality. “I remember sitting there and typing up everyone’s merch orders,” the 36-year-old reminisces as he shows me around his first “recording studio” — really his father’s backyard shed, which Scrim outfitted with cheap speakers and a laptop back in high school. It’s nearly 100 degrees on this June day in suburban Lacombe, La., and the shed’s window AC unit is coughing out cool air as hard as it can, but it seems to make no difference. It’s just that hot.

“We used to do everything,” Scrim recalls of $uicideboy$’ early days. “Everything!” interjects Aristos “Ruby Da Cherry” Petrou, 35, Scrim’s bold, charismatic cousin and the other half of $uicideboy$. “The album artwork, designing the merchandise, making the beats — which we still do — making the videos, that was all us.” The two often finish each other’s sentences.

Over a decade into their career, $uicideboy$ have become one of the most successful and lucrative underground (if you can even call a group that sells out arenas that) acts around, and while they’ve since outsourced the post office gig, Ruby and Scrim still helm the whole operation. They are the proud co-founders of their own label, G*59 Records, which did an eight-figure distribution deal with The Orchard in 2020; their annual multi-artist Grey Day Tour (think Warped Tour but more hardcore and rap-oriented) grossed $50.7 million last year, according to Billboard Boxscore; they built a merch business that made over $30 million in 2024 alone, according to their team. And since 2016, they’ve done it with the help of co-managers Dana Biondi and Kyle Leunissen, who ensure Ruby and Scrim still have time for the most essential part of it all: the songs.

Amazingly, they’ve achieved all that without cracking the Billboard Hot 100 until their 2024 album, Longterm Effects of Suffering, which yielded four songs in the lower 30 slots of the chart and no radio airplay hits. On the Billboard 200, they’ve fared much better, notching four top 10 albums.

But around 2019, all of it — the indie-music empire, relentless schedule of making songs, going on tour and managing the label — nearly came crashing down when Scrim finally decided he needed a break to get clean from the assortment of drugs he was taking on a daily basis. “I went to treatment, and I was out in [California] for what, nine months?” he recalls, looking to Ruby. “Then I went in 2020 in October,” Ruby adds. “I was out there for about six, seven months. So he got his break. I got my break, which I would argue wasn’t really a f–king break, considering we were getting off drugs and we were relearning how to live life.”

Post-rehab, the duo — named for its blood oath to “give ourselves ’til 30” to make its music career work “or we would kill ourselves,” as Ruby explains — was left to answer a challenging question: What would $uicideboy$ be if they got clean — and maybe even got happy?

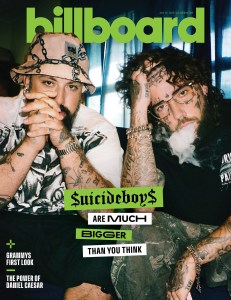

Ruby da Cherry (left) and Scrim of $uicideboy$ photographed June 20, 2025 in New Orleans.

Akasha Rabut

There was no guarantee it would still work. The two enrolled in what they jokingly call “marriage counseling” to get through it. “This is like a marriage, and it was helpful. [We did it] with management, too,” Scrim says. With their drug-fueled days behind them (though Ruby still smokes cannabis), the two had to “relearn how to make music” sober, as Scrim puts it; find their faith in a higher power; and rebuild their lives.

Five years later, the two cousins speak to Billboard as they have discovered the fruits of this rebuild. Their latest album, Thy Kingdom Come, planned for an Aug. 5 release, chronicles the latest chapter of their journey, including “hardships of being on the road, loneliness, getting old,” Scrim says. Soon after, they will embark on the latest Grey Day Tour, and rumors are circling of a catalog deal, which sources tell Billboard could be worth $300 million or more (while Biondi recently acknowledged to Billboard that “something firm” is in the works, the team declined to provide an update).

But more than any accolade, $uicideboy$ are most “grateful to be alive,” Scrim admits. “Honestly, I never thought I’d get here.”

There is a framed portrait of Saddam Hussein made out of LEGOs on Ruby’s living room wall. “I put it up to make sure y’all get it in the shot,” he says with a laugh to me and the Billboard camera crew when we visit his house in the 7th Ward of New Orleans. He used to live in this unassuming ranch-style home, but now he splits his time between a different house in town and a place in the Florida Panhandle. He likes to go there with his girlfriend when the beachgoing tourists leave: “[I like] when it’s almost a ghost town. It’s a very simple life.”

Ruby held on to this house, however, to turn it into a state-of-the-art recording studio and overall dude wonderland. Along with the music gear a studio requires, the walls are painted various neon shades, and the place is littered with Sopranos memorabilia (his current rewatch tally: 23), Pokémon plushies, Hot Wheels cars and vintage Pac-Man consoles. The place looks like the inside of Ruby’s brain — fun-loving and obsessive, with a twisted sense of humor. He’s also got a “gay frog” he bought as a joke from InfoWars, a collection of DVDs he did not buy (“I stole them”) from a video store where he once worked (he claims it was run by the mob) and a very… imaginative painting of a prison cell where Hillary Clinton has Jeffrey Epstein in a headlock.

Most importantly, the house has AC.

As he shows me around, Ruby explains how he developed a fascination with dictators like Hussein and collects memorabilia of them — a possible result of his addictive personality. “They fascinate me,” he says. “Obviously they’re horrible people who committed atrocities, but the idea of how power affects someone like that is so interesting.”

Ruby da Cherry

Akasha Rabut

Ruby grew up playing drums in punk bands, despising authority and always looking for a way out of the nine-to-five slog he figured awaited him in adulthood. He recalls being frustrated with early bandmates who weren’t as determined or invested as he was and the teasing he endured for caring so much about music. “It wasn’t cool to step out of the lines,” he says.

After finishing school, Ruby called his cousin Scrim, who was at the time becoming a popular local DJ and producer. “He was the only person that every time I said, ‘Let’s do this today,’ he was down,” Ruby says. “I’d argue that’s what separates us from a lot of people. Even if it’s not convenient for us, we just do it because we love to do it. Doesn’t matter the time, place or whatever.” Scrim adds: “It didn’t matter [what was happening], we got it done. I was in here with no excuses — withdrawing, detoxing, whatever.”

The DIY punk ethos fueled their early career, when the two would stand on street corners at Louisiana State University (they weren’t students there) handing out mixtapes. “Then we’d walk 10 feet and see every CD we just handed out [in the trash],” Scrim says with an eye roll. Ruby also recalls a list of “a thousand rap blogs” he made and reached out to. It yielded two write-ups.

Then, one day they went over to Ruby’s friend’s house: “[He] pulls up YouTube and then pulls up Yung Lean, Xavier Wulf, BONES, Ugly Mane, and I’m like, ‘What the f–k…?’ We just weren’t familiar with the new underground SoundCloud thing that was going on. We were doing things in an ancient kind of way… I remember leaving the house and my mind being so f–ked up,” Scrim says. “That’s when everything changed. That’s when we started attacking the internet.”

With the first 10 volumes of its Kill Your$elf mixtape series (titles include Kill Your$elf Part I: The $uicide $aga and Kill Your$elf Part IV: The Trill Clinton $aga; the latter’s artwork features its namesake in sunglasses, blowing on a saxophone, overlaid on an American flag) released in 2014 and 2015, the two began to amass a fan base of struggling misfits just like them and fed the fandom with limited-edition merch drops, a la Supreme, which Ruby designed himself. Scrim was more the numbers guy — that’s what led him to keep track of addresses at the post office, sending packages to fans around the country himself. “He also had a checkbook balanced to the penny,” co-manager Leunissen says. “He’s a perfectionist when it comes to that stuff.” The cousins worked as if their lives depended on it — because really, they did.

Akasha Rabut

Leunissen and Biondi joined the team in 2016. Leunissen, a friend of Scrim’s since high school, was working as a sports agent in Atlanta, and Biondi was an artist manager for up-and-coming rappers, in search of his next project. In hopes of helping out his friend Scrim, Leunissen told Biondi — one of his few connections to the music business — about a show $uicideboy$ were about to play at the Roxy in Los Angeles. Biondi went and was immediately taken by the energy $uicideboy$ stirred in the crowd.

“When I got started in the business, it was mostly weed rap,” Biondi says. “Very hug the wall, look cool, smoke your joint kind of stuff. When I walked into that show, the kids were mosh pitting, and I was like, ‘S–t, this is different. It’s a punk show, but it’s rap.’ ” The cousins have been known to take turns with their verses onstage, rapping and screaming out to the crowd, stoking their fans’ pent-up frustrations and turning it into a mad, kinetic energy. “I’ve always been a rap guy and thought, ‘This is the future of the genre.’ I needed to figure this out, and I called Kyle, saying, ‘Let’s partner up.’ ”

Biondi wasn’t the first to reach out. Around that time, he recalls, other savvy A&R executives and managers were circling the duo, too. Ruby says that the labels approaching $uicideboy$ back then were “much more aggressive” with their deal terms “before we had managers,” perhaps sensing the pair’s vulnerability. The cousins realized they needed some help, but they weren’t convinced a label was the right fit.

As Scrim told Billboard in 2021, Leunissen pitched the rap duo on the foursome working together by saying, “ ‘You’re letting 70 grand fall through the cracks every year.’ That caught our attention,” Scrim said. “For my cousin and I, $70,000 might as well have been a million at the time.”

Scrim

Akasha Rabut

“We still explored all label options,” Biondi says. “It just became pretty clear that between them just being unreal at what they do, and then us being able to provide the back end that was needed, that the best fit was doing it all ourselves. Also, I think it was just those contracts from 2016 to 2017 were just so locked down, so 360. It was scary to meet somebody a couple times and then sign three, four or five albums away and be like, ‘Let’s just see what happens!’ I saw that the industry was changing, and we wanted to try to build it ourselves.”

It was a prescient call. Within five years, major labels began to move away from offering 360 deals for competitive signings and instead even gave some top signing priorities ultra-friendly licensing deals allowing them to regain their recordings from the label after a set number of years. Meanwhile, the market started to shift in favor of a growing cohort of artists across genres, like $uicideboy$, who along with the support of their managers were doing it all on their own.

For about a year, Leunissen recalls, $uicideboy$ remained on TuneCore, the DIY distribution company that allows artists to pocket 100% of their royalties for a small upfront fee, and they continued to build their brand. “We did 120-something shows in that first year or so, and the money coming in [from TuneCore] really helped fund everything. We would distribute the payments to them, and the business was running along,” Leunissen says. In 2017, they launched G59 Records with distribution from Virgin, and Ruby and Scrim used the platform to sign their contemporaries, like Germ, Chetta, Shakewell and Crystal Meth.

G59 signees benefit from a number of special perks. Scrim and Ruby say they often offer feedback to their roster, when requested, or feature on their tracks to help them build momentum. Signing to G59 also tends to mean being first in line to get a slot on the Grey Day Tour, placing the new artists in front of captive audiences and beside other, bigger acts like $uicideboy$, Turnstile and Denzel Curry.

By 2020, $uicideboy$ still hadn’t charted a single Hot 100 hit, but their robust merch, touring and streaming success made them impossible to ignore. Sony’s distributor The Orchard came calling, offering the G59 crew an eight-figure sum to move the label over to it. With newfound clarity from their stints in recovery programs and so-called “marriage counseling,” the rejuvenated and rehabilitated $uicideboy$ took the deal and have since re-upped to another term in 2023.

Ruby’s coffee table

Akasha Rabut

The Orchard’s CEO, Brad Navin, tells Billboard his first impression of the duo was simply: “What is this?” But after diving deeper into what made the band tick, he found a “highly engaged, highly loyal” cohort of followers driving its formidable business. It was unlike anything he had seen before. “$uicideboy$ are unique in every way, as both entrepreneurs and as artists,” he says. “They tend to avoid the mainstream at all times… But they have an acute understanding of who their fans are, and everything they do is with their fans in mind. That’s what makes them so powerful.”

“I think from the beginning, our goal was to have a cult-like following,” Scrim says, getting out a pink vape while he speaks. “Ruby helped me see that that was the way.” It’s still rare to see $uicideboy$ get mainstream accolades — they do little press, don’t court radio programmers, don’t use TikTok and have yet to achieve a Grammy Award nomination — and for the most part, that’s OK with them. “I think it’d be cool to win a Grammy, but it’s not something that we’re banking on or something we’re actively trying to achieve,” Scrim says. “If it happens, it happens. But, I mean, I don’t think that’ll ever happen. No matter what… we just don’t get a lot of industry recognition.” Ruby adds: “Honey, we ain’t worried about it either.”

For them, looking out at the arena-size crowds each night on an annual tour they made in their own image is still an incredible outcome. “It’s obvious that we made it,” Ruby says.

“I know there’s somebody in here tonight — I don’t know who — who’s struggling,” Scrim says. “If you’re in that spot and you feel like s–t’s hopeless, you feel unloved, misunderstood, unworthy, whatever the case may be, I’m here to ask you, from me and Ruby, if you can’t do it for yourself, do it for us: Don’t ever, ever give up.”

The crowd at Las Vegas’ MGM Grand Garden Arena last September roared — as it does every night when Scrim closes out the act’s notoriously raucous show with this speech. It’s become a tradition by accident. Overcome with emotion one night, a newly sober Scrim decided to speak off the cuff at the end of a set. “It just became this thing that I continue to do, but I do feel… like when Lil Wayne was getting high — I’m not blaming him — but [as a fan], I did it, too, and I remember when he had that period where he put out a mixtape and he was getting sober, so I tried to get sober. It had a real effect on me because I idolized this guy.” He knows that for his fans, he holds the same stature.

Akasha Rabut

As the two continue in their recovery, Ruby and Scrim have both become much more reflective about what $uicideboy$ means, and whether they can turn their fans’ fervor into lifesaving outcomes. While the point at the beginning of their career was to make music that “flexed their own misery,” as Ruby has joked, but didn’t glorify it, and to create a community for struggling kids and iconoclasts to bond over voicing the hard, and often distasteful, truths of depression, the power they wield still clearly weighs on them.

Now they say they’re on a mission to do what they can to “save 100,000 souls before [we] leave this earth,” says Ruby, who, like Scrim, has gotten more in touch with his faith since going to rehab. “I think at one point it seemed like, in 2016 to 2017, everybody was on drugs… and we felt like we opened this box [with our music] that we weren’t supposed to open,” he continues. “It was never like, ‘Hey everybody, go do heroin, it was great.’ It was more like, ‘This is what the f–k we do…’ We were very unapologetic.”

On new album Thy Kingdom Come, $uicideboy$ won’t shy away from the dark subject matter that got them where they are now, but they’ve become far more thoughtful about how they go about it. Now in their mid-30s, Scrim and Ruby say they have witnessed the first signs of aging and mortality — the constant jumping around onstage isn’t as easy as it once was, Scrim laments — and life is different: Scrim’s married, Ruby’s in a serious relationship, they work out every day, and they’re more committed than ever to their work. “You know, it’s funny, because I spent most of my life wanting to kill myself,” Scrim says with a bemused look as he describes his current gym routine. “And now I’m terrified of dying.”

Look up “Suicideboys” on TikTok (without the dollar signs) and you’ll find just one result: a suicide prevention message that reads, “You’re not alone. If you or someone you know is having a hard time, help is always available: View resources.” I ask Ruby and Scrim about it, and whether online safety blocks for words like “suicide” ever made them reconsider the name, whether for business purposes or for sensitivity. “I did recently, actually,” Ruby says, turning to Scrim. “I don’t know if I told you this. But then I personally was like, ‘Yeah, f–k that.’ At the end of the day, we don’t do this for followers… at the end of the day, it’s not about us. And I think fans would get upset if we changed our name. I like that when you search it, it’s like, ‘Are you good?’ ”

“To me, it represents…” Scrim adds, pausing to consider his words. “I don’t even know where to start. It represents so much.” As usual, Ruby finishes his thought: “It represents our unwillingness to conform.” And Scrim agrees. “And it shows the dark s–t we came from to the way we are now. I mean, it means so much.”

If you or anyone you know is in crisis, call 988 or visit the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline’s website for free, confidential emotional support and resources 24/7.

This story appears in the July 19, 2025, issue of Billboard.